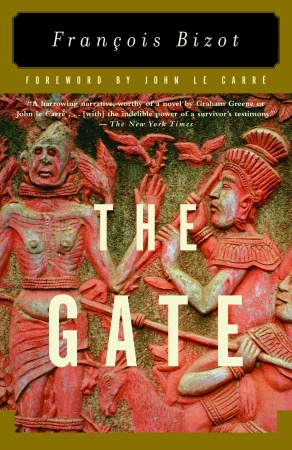

The Gate by Francois Bizot (Vintage Books/Random House)

Francois Bizot was a Khmer-speaking Frenchman, an ethnologist who searched for old manuscripts and art that would illuminate the religion and customs of ancient Cambodia. A man whose only gods were Saul Steinberg and Charlie Parker, Bizot lived in a village near Angkor Wat with his Cambodian wife and their little daughter. His world was “enameled with paddy fields, dotted with temples, a country of peace and simplicity.” Then the war in Vietnam spilled over the border into Cambodia and Bizot and his family moved to the urban safety of Phnom Penh.

While working thirty miles from Phnom Penh with two of his Cambodian colleagues, Bizot and his companions were captured by a group of Khmer Rouge. They marched at gunpoint for three days to a remote village, where they were confined on their backs, their ankles shackled within two wooden beams. As they lay there alone and in pain, they could hear the sound of bare feet approaching and a group of young girls, “pretty,” Bizot noted, “ just like those from my own village,” surrounded them and spat on their faces.

The man who was in charge of this Khmer Rouge outpost was young, thin and suffering from malaria. “His authority was total. His silences were mightier than words.” Repeatedly he came to Bizot with pen and paper to receive written declarations of innocence. Bizot's statements were written in French but the conversations that he began to have with his jailer were in Khmer. “The bonds gradually forming between us depended entirely on our capacity to understand each other on common ground and this could be done only in his language.”

It was Bizot's ability to communicate in Cambodia’s language that convinced his captor of his innocence and prompted this man to persuade the Khmer Rouge leadership that the Frenchman should be freed. After three months of imprisonment, living in shackles, witnessing death, and experiencing humiliation and torment, Bizot was released. No other prisoner left that camp alive; his Cambodian colleagues were executed after his departure, despite assurances from the leader of the camp that they would be safe.

Four years later, the Khmer Rouge took Phnom Penh. The Americans had fled, Bizot had sent his daughter to France, and his wife joined the crowd of Cambodians who were ordered to evacuate the city.

Sent to the French embassy with all other foreign residents of Phnom Penh, Bizot used his Khmer language skills once more to advantage, becoming the link between the Khmer Rouge leadership and the foreign community, and the only foreigner authorized to leave the embassy walls. His descriptions of a city emptied of its inhabitants and of the Cambodian people who were denied the safety that lay behind the gate of the embassy are haunting and soul-wrenching.

Long after the Pol Pot years had passed, Bizot returned to visit Cambodia. The camp where he was held has become famously known as Anlong Veng and is now a tourist attraction. The man who held him prisoner and was responsible for his release is known to the world as Douch, the infamous leader at Tuol Sleng, the Phnom Penh high school that was turned into a center of torture and death. Bizot’s history, lived in Khmer, written in French, and translated into English, provides stunning testimony to whatever International Tribunal may someday stand in belated judgment.~Janet Brown