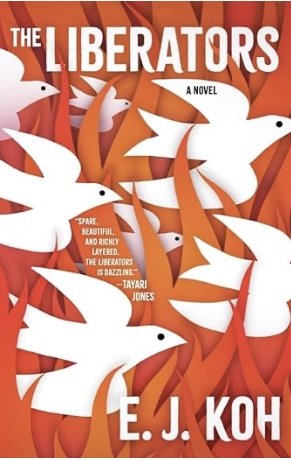

The Liberators by E. J. Koh (Tin House)

“The fog drew rosefinches, like blooms in the low bush, whose cries I mistook for rainfall.”

Yohan is a man obsessed with words, who can write them in six languages. During his lifetime, he has lived through the Japanese occupation of Korea, survived the horrors of World War Two, and “watched the country divided up as spoils of war.” What puts him into prison is a shadowed mystery with a partial disclosure: “To be a spy was to one day be known.”

Decades later, living in America, his daughter meets a man who draws a tiger on her bare back and tells her “It’s Korea,” “if the country had no stitches” and was reunified as a single nation. Although he knows “The South doesn’t want to rebuild the North. And the North doesn’t trust the South,” he is devoted to bringing the two divisions back together once more. His dream is rejected by the Korean men who come to his meetings in a local pool hall and when he returns to Korea, he’s imprisoned “for crimes of moral turpitude.”

Although politics is a hopeless quagmire that gobbles up idealism, Yohan’s daughter erases divisions in her own family by nurturing her North Korean daughter-in-law. When she dresses the mother of her grandchild in the green hanbok that was once worn by her own mother, “the fabric folded smoothly..,the ribbon falling down the front, a new verdant path.”

Like Yohan, E.J. Koh is dominated by words. In her memoir, The Magical Language of Others (Asia by the Book, November 2020), she describes her life, lived in four languages, English, Korean, Japanese, and poetry. “Languages,” she says, “as they open you, can also allow you to close.”

In her first novel, Koh lets the language of poetry open windows and then it slams them shut. Six characters are partially revealed in The Liberators but none of them are as fully realized as the images that surround them. In a gorgeous section entitled Animal Kingdom, Yohan’s grandson is given a dog, “a bright and curious joy,” that’s “joined to the boy like a wish.” Later the boy is united with the woman he will marry in “the elaborate braid of our bodies.” Trapped in poetry, he and the other five characters that fill these pages remain “shadows that flew up and shattered across the ceiling.” Each of them is truncated by subtlety, as if they were created to convey Koh’s language rather than the reversal that would have given them life. They are pieces in a jigsaw puzzle, given just enough definition to merge into a whole pattern.

Mixed with Koh’s poetry is the harshness of political realities in which a country with millennia of history and tradition becomes sacrificed to global economic interests. When Koreans gather together in America to watch the TV coverage of the Olympic ceremony in Seoul, the doves that symbolize world peace perch on the flaming cauldron and are burned alive, “a memory that had to be erased…that had to be forgotten in our soft, closed palms.”

“Why visit the past, why go digging up its grave?” asks the man who dreams of Korea as a tiger, complete and undivided. Yohan’s daughter answers him by embracing the present in another country, unified with her North Korean daughter-in-law, a conclusion that escapes cliche because Koh has clothed it in poetry.~Janet Brown