A Field Guide to Happiness : What I Learned in Bhutan about Living, Loving and Waking Up by Linda Leaming (Hay House)

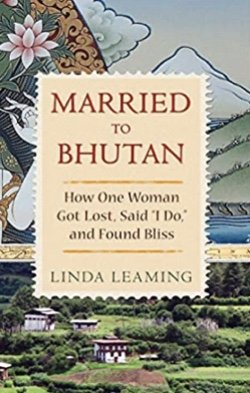

Linda Leaming was a young American woman who left her comfortable life in Nashville, Tennessee and went to the small Himalayan country of Bhutan, the country known for its Gross National Happiness, to teach English. Not only did she fall in love with the country but she fell in love with one of its citizens and started a new life there. She wrote about it in her first book Married to Bhutan (Asia by the Book, November 2021).

Leaming has now written a follow up book titled A Field Guide to Happiness with the subtitle of What I Learned in Bhutan about Living, Loving and Waking Up. Leaming has lived in Bhutan since 1997. She married a renowned thangka artist, thangka being a religious painting usually depicting a Buddhist deity. She now shares what she learned and continues to learn in Bhutan about finding happiness.

When Leaming talks about happiness in this book, she says she’s talking about well-being. She thinks of happiness as “being a state wherein we are ‘without want’”. Her four main points of what she thinks about happiness is, first, “Everyone wants to be happy.” Second, she believes “happiness begins with intent.” Her third point states “Happiness doesn’t just happen; it’s a result of conscious action (and sometimes that “action” is to do nothing).” Finally, she believes “this action involves doing simple things well”.

One of the first things she says she had to learn was patience. This was before she got married and became more grounded in living in Bhutan. Her first visit to the Bank of Bhutan was emotionally challenging as she was the epitome of an American living in a foreign country. Americans are those people known for being busy, loud, obnoxious, demanding, and impatient. Perhaps it is an unkind stereotype but it may be an accurate description. She says, “In Bhutan, if I have three things to do in a week, it’s considered busy. In the U.S., I have at least three things to do between breakfast and lunch.”

Living in Bhutan has taught her more about herself than she would learn from any psychologist or self-help book. She has learned to be more patient, to “go with the flow”, to do without the modern conveniences of America, such as buying groceries at a supermarket or having a washing machine to do the laundry. She has learned to love and accept herself for who she is, she strives to be a kinder and generous person to others, and she can now talk about death without fear.

To say this is a self-help book would be an overstatement. Leaming doesn’t push her beliefs on others, she just shares what works for her. She tells her stories in a way that’s delightful and amusing and never condescending. She shares her own weak points and tells the reader how she tries to overcome them or at least not worry about them as much as she used to. What works for Leaming may not work for everyone but I believe as Leaming does, that everyone just wants to be happy. ~Ernie Hoyt