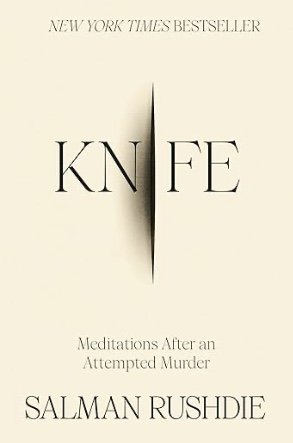

Knife by Salman Rushdie (Random House)

In 1988, Salman Rushdie became a symbol. His fifth novel, The Satanic Verses, enraged the Muslim world and led the Ayatolla Khomeini, the Supreme Leader of Iran, to call for his assassination.

A fatwah was issued, a legal decree that is irrevocable. It guarantees that as long as Rushdie draws breath, he can be murdered with impunity, under Shia Islamic law. It also guaranteed that to millions of people, Rushdie was a target while to millions more he was an icon of free speech.

A target? An icon? When Rushdie decided to live without fear and with pleasure, then he was derided as a “party animal.” It took him almost thirty years to find a place where he could be happy and escape the different narratives that tried to put him in an assortment of pigeonholes. He was, he said, “famous not so much for my books as for the mishaps of my life.”

Then, six years later, soon before his twenty-first novel was released, he went to speak at the Chautauqua Institution. An idyllic spot in rural New York, this is a place that, for 150 years, has dedicated itself to ideas, thoughts, and discussion that would foster the growth of a civil society. It’s a sanctuary that has never seen violence. So when a man burst out of the audience as Rushdie began to speak, nobody moved in the minute or two that it took the assailant to reach the stage. Until he pulled out a knife and began to stab, 27 seconds passed before someone realized this was not performance art.

In under half a minute, Rushdie is almost mortally wounded in an attack that would change his life once again, trying to pin him to a fate that was prompted by somebody else’s actions. He’s 75 years old. It will take him six weeks to leave his hospital bed and far longer than that to undergo agonizing therapy. “You’re lucky,” a doctor told him, “that the man who attacked you had no idea how to kill a man with a knife.”

But the flawed attack puts Rushdie in “a one-eyed, one-handed world.” The simple act of tooth-brushing becomes an ordeal and before his left hand is mobile again, a therapist has to chip away at a thick layer of dried blood. His right eye is gone forever. The knife had reached the optic nerve.

But even when he was comatose, Rushdie’s creativity was brilliantly alive. Unconscious, he envisioned palaces whose building blocks were the alphabet and when he finally opened his surviving eye, he saw golden letters floating between his bed and the people who stood beside it. From the very beginning of this, he knew that although “the knife had severed me…language was my knife.”

Unable to return home for security reasons once he’s released from the hospital, he still has his “home in literature and the imagination.” He claims his story and reclaims his life. He writes Knife.

Reading this book is a humbling and inspiring experience. Rushdie’s language is playful and discursive, thoughtful and creative. Being given an entrance to his mind and trying to keep up with him is dizzying and sometimes vexing, and his story, told without a softening filter, is often harrowing. But it never lapses into self-pity. A man who was brutally forced out of the life he had created takes full possession of where he has been put by someone who attacked him as a symbol that was “disingenuous.” In his mid-seventies, Rushdie seizes his “second chance” at being alive without clinging to “ an irretrievably lost past.” In his old age, this ageless artist continues to “sing the truth and name the liars.” ~Janet Brown