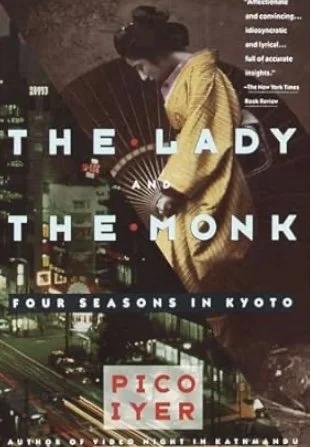

The Lady and the Monk by Pico Iyer (Vintage) ~Janet Brown

Who can explain why a country that we’ve never known can call to us? Pico Iyer, a man of many backgrounds, felt an inexplicable affinity for Japan from childhood onward. Without ever having been there, it always felt like “an unacknowledged home” and when he spent a long layover in the town of Narita while on his way to Southeast Asia, what he saw was much like his boyhood in England. “A sense of polite aloofness” in “an island apart from the world,” “an attic place of grey and cold” where “polished courtesies kept the foreigner out” all felt very British. Iyer, “with no plans, no contacts, no places to live,” came to Kyoto with two suitcases, hoping to live a solitary life of learning and exploring the spiritual life in Japan.

Spending his first weeks in a temple, Iyer discovers that the temple is “ringed by love hotels. “A wonderland of indulgences” is only five minutes away, where streets explode with pachinko parlors, convenience stores, and shopping malls. Soon he finds a room on a narrow lane in a residential neighborhood that’s occupied almost exclusively by women and children. Iyer is probably the only male in the area who doesn’t spend his working hours in an office.

Kyoto, he says, more than almost any other city in Japan, is “self-consciously Japanese,” a “repository of the country’s female arts and of the spiritual life found in temples…a city defined by monks and women.” So it’s almost inevitable that on a visit to a temple he meets an elegant Japanese lady who invites him to come to her daughter’s birthday party.

Iyer is in love with Kyoto by now, wrapped in “the blue intensity of knowing nothing but the present moment.” His senses sharpened, he finds that living in “a flawless world shook me out of words. Still his descriptions are precise and painterly, seeing “the moon a torn fingernail in the sky,””the sky a burnished strip of gold and silver,” and autumn as a series of “tidy daily miracles” with “drizzle softer than a silk still life.” He becomes enthralled by Japanese classic literature in which poetry and its two most famous novels, The Tale of Genji and The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon were written by women. “Enameled perfection,” Iyer describes this, “poetry of the paper screen.” In Japanese, he’s told there are “different colors for each wind, different words for moonlight on water.”

It’s an easy step to go from this deep infatuation with a culture to a fascination with the one person who opens this culture for him. The elegant lady quickly reveals her restless spirit in English that is as articulate as it is charmingly flawed. She longs for Iyer’s freedom. He becomes enthralled by her quick intellect and her delightful candor. A prisoner of her traditional culture, Sachiko welcomes the opportunity to leave her household and take this foreigner to places she’s never been able to visit until now. She’s a fearless speaker of English and Iyer is eager to use the Japanese language in which he’s still a beginner so their conversations are “three-legged waltzes” in which emotions take on a greater prominence. While they discuss Herman Hesse and Emily Bronte, they forge a form of intimacy that neither expected.

The Lady and the Monk is a book that only carries a special meaning if the readers know the life that Iyer has now. Without that knowledge, it ends on a note reminiscent of Madame Butterfly, with Iyer leaving Japan and Sachiko embarking on a new life without him. In truth, this is an introduction to their life together in Japan and should have included an afterword to this effect. But even without that, this scrupulous and lyrical story of a double-barreled love affair, with a country and a person, is told with delicacy and grace, leaving readers with this question. Where is your own “unacknowledged home” in the world?