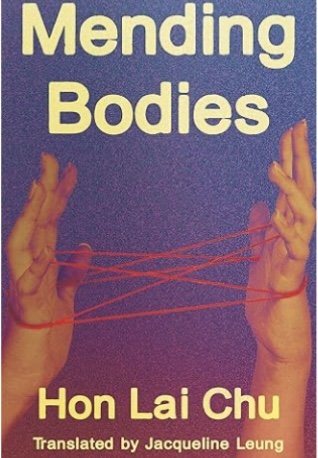

Mending Bodies by Hon Lai Chu, translated by Jacqueline Leung (Two Lines Press) ~Janet Brown

Back in a distant decade I edited a series that had been translated from Chinese into English. The books were comprehensible but almost every sentence needed to be rewritten, something I had never done before as an editor. When the review comments began to stream in from people who had read the saga in Chinese, it became clear that much of the lyrical quality that had made the books a sensation in their native language was gone in English, completely lost in translation.

For a long time I had read contemporary Chinese literature and had decided I disliked it. After my editing experience, I realized what I had disliked were the translations done by Howard Goldblatt. After I finished reading that man’s translation of Jiang Rong’s Wolf Totem, I met the publisher who had come out with a Thai translation of the novel, a woman who had read it both in English and Chinese. “The Thai translation is better,” she told me.

I’ve never approached fiction in translation in the same way again. A translator, I’ve decided needs to be a writer who respects and conveys the feeling behind the words, as well as their exact meaning. If that doesn’t happen, the novel is flat and lifeless.

With this always in mind, I often read a translated novel wishing that I could read the original work without an intermediary, a feeling that haunted me as I recently read Hon Lai Chu’s Mended Bodies.

In an unnamed island city, the Conjoinment Act is changing the basis of the primary social contract. Individuals of the proper age are matched with another person of the opposite sex and the two are stitched together, quite literally becoming one flesh. The couples take new names and are given a common identity card. They lose any vestige of privacy and can escape each other only when they’re sleeping.

The surge of conjoined couples revives the economy, as they launch a need for medical professionals, filling hospital beds and therapists’ offices post-surgery. Clothing, cars, furniture, are all redesigned for the altered bodies. Employment figures soar.

The newly instituted law evokes controversy. Some maintain its necessary in order to reconfigure failing social norms, while their opponents claim conjoinment is in place to distract people from “a long campaign for the city’s independence.” Others say it reduces the environmental evils that come from overpopulation. But in spite of the various opinions, nobody actively agrees or disagrees. “A certain ambivalence toward policies we had no control over was the last effective resort for protecting our remaining freedoms.”

This is the thought of the young university student whose dissertation is on conjoinment throughout mythology and history. Unsure of her conclusion, she finds a mate through a body-matching center and the two of them are stitched together. Unknown to her husband, this woman has chosen conjoinment as an experiment that will help her to advance her thesis.

“It’s both of us or neither of us,” her husband says after the surgery is over. He’s convinced this is the death of their individuality but his wife soon knows “we never asked what the other person did while we were asleep.”

As she continues her study of historical conjoinment, she realizes the artificiality of the stitched bodies and the impossibility of a manufactured union. To continue her exploration, she drugs her husband into unconsciousness and, struggling under his dead weight, visits her aunt who chose to be separated after conjoinment, and the university professor who is her dissertation adviser. Slowly she discovers the conclusion that’s eluded her and she makes her choice.

An allegory that lacks subtlety, Mending Bodies never comes to life. It drowns under images that are poorly conveyed by someone who has no gift for rhythms in sentences nor for dialogue that is unstilted. One character bites into “a dank piece of tuna.” Another “knits her brows.” Descriptions miss their mark and become comic, “an afternoon in plum rain season, lush mold blooming all around.” So many promising images go awry, speeches become clumsily polemical, and I blame the translator. Let’s hope that Hon Lai Chu finds a better one for her next foray into English.