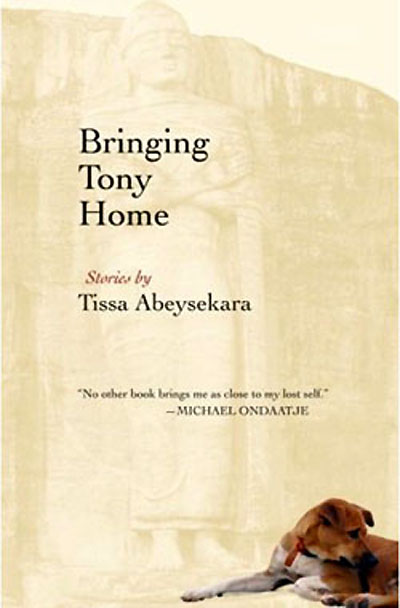

Bringing Tony Home by Tissa Abeysekara (Scala House Press)

Kristianne Huntsberger, a soon-to-be Bangkok resident, looks at memory and identity through the eyes of a Sri Lankan writer.

The epigraph to Bringing Tony Home is taken from a dialogue with the Buddha, in which a man asks, "If I die and am born again as you say I will be, is that, which is reborn, the same me?" The Buddha replies that it is "neither you, nor yet any other." Tissa Abeysekara writes that, likewise, his book, "being truth recreated through memory, is neither true nor untrue." It is a collection of stories grafted with autobiography. Memory and fiction come in and out of focus the way that a sweeping camera pans over an expansive landscape where a small figure traces a road along the railroad tracks.

Locating identity within memory and the recorded history of his mid-twentieth century home in post-colonial Ceylon is a daunting task for the narrator, a boy from a privileged native family whose fortunes failed after World War II. He recalls a British fighter plane crash in 1942, and his memory of watching the wounded pilot being carted away in a hackney. His mother considers this a constructed memory because he had been only three years old "and according to her it is not possible to remember that far back and over the years I came to doubt it myself, but now I remembered the scene once more and it seemed quite real and if it was otherwise like Mother suspected, it didn't seem to matter anymore.". The family is forced to leave behind the "Big House" and the red Jaguar and Tony, the faithful family dog. The boy's mother would have him learn to adapt and his father would have him hold on to the former world. These stories explain the consequences of this division, evidenced in the narrator's internal and social struggle. When revisiting the native home of his grandmother he encounters a monk on the mountain who asks, "'from where are you?' This question in my language implies much more than your place of residence. It wants to know your origin." This is the question the narrator pursues and the one that provokes the deep introspection of Abeysekara’s stories.

When the narrator rescues his dog, marching him the distance between the abandoned Big House in Depanama and the poor one in Egodawatta, or when he rejects his father’s gift, rediscovers his adolescent lover or travels to the central hills where his grandmother was born, we understand that we are being shown more than just these incidents. We are following the narrator as he learns, finally, the meaning behind the episodes in his life. There is clarity in the distance he has gained and in remembering things past, much like glimpsing the sea from the mountaintop. As the monk he encountered near his grandmother's home explained, after years of looking, it will happen suddenly: "through that little break in the long line of hills, like through the eye of a needle, I saw the water, blue and glistening like a crest gem. Ever since then I see it. I need glasses to read, but I see faraway things." Abeysekara paused in the middle of his life to reflect on a world he no longer recognized and which had ceased to recognize him, and to glimpse the world he was unable to see before that moment.

After receiving word that Abeysekara had passed away in April of this year I re-read Bringing Tony Home. Returning to the book as tribute to the man's nostalgia, I found my own. Between the pages I had left a bus transfer and a strand of hair--a gray one--that I lost while reading a passage in which the narrator unpacks the story of his own birth, faced with entries from the diary his father kept that year. How does one react to the unraveling of one’s own myth? By recognizing the contradictions of our fathers as our own, Abeysekara answers. The relationship then between fiction and fact in these stories is the same as in the lives we live. We re-member and re-read and re-live our memories to make meaning.