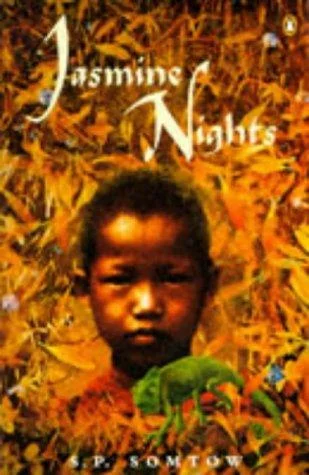

Jasmine Nights by S.P. Somtow (St. Martin’s Press)

jasmine2

When I worked at the Elliott Bay Book Company I was always in search of titles to recommend for twelve to fourteen year old boys. These recommendations had to be something more than the popular wizard series or the classic adventures of Verne and Kipling, whose language could be difficult for some young readers. If I were working at that bookstore now, I would be sure to have Somtow’s novel on hand.

Though not billed as a young adult book, Jasmine Nights is a perfect fit. The hero, Justin, is nearing thirteen years of age and learning the life lessons imparted by his crazy family, his crazy morphing body, and the crazy world in 1960's Bangkok where he has been deposited by his parents and where he learns about friendship, love, family and himself.

Inspired by his spunky and irreverent great- grandmother, Justin begins planning his Pinocchio transformation into a real boy. His first adventure on this course belies how far he has to go to meet his goal, which lies somewhere at the end of a list including tree climbing, swimming naked in the khlong and saying nasty words, “whose meaning I am only now starting to guess at.” His first act is kleptomania, but his shoplifted object is a Penguin Classic copy of Ovid’s Metamorphosis. Justin’s journey continuously skirts this line between his romantic, literary inclinations and his directed assimilation into even the darkest corners of the “real world.”

Like climbing trees and skinny dipping, issues of race, class and cultural conflict have never before entered Justin’s imagination until he met his African American neighbor, Virgil and becomes attracted to Virgil’s natural boyishness and his commitment to the young and painful cultural history that his family carries. It is the painful portion of Virgil’s heritage that takes the stage as the expat children begin their school year and racial tensions flare.

When Justin discovers that a Boer classmate’s best friend back in South Africa was black he asks why, then, should he and an American boy from Georgia be so cruel to Virgil. It’s different, the American boy explains, “I used to hang out with [black children] too, sometimes, but they knew better’n to piss in the same toilet or sit in the front of the bus. It ain’t that I’m prejudiced or nothing, Justin, it’s just, well, we don’t belong together.”

Justin is overcome by it all and by his own participation in the classist prejudices of his culture, noting that “there is a terrible wrongness in the world but that I am powerless to correct it. There is a disturbance in the dharma of the cosmos.”

Luckily, the book does not flatten the issue. Justin sees that, above all, it isn’t an easily definable problem since each of the boys “is the victim of a self-perpetuating cycle of injustice.” It isn’t the fault of any of them individually, he notes, “It’s the whole forsaken universe, locked in a maze without doors, all of us, each one of us and island, each one of us alone.” As part of his transformation, Justin takes it upon himself to right these great wrongs.

Perhaps the most significant weight that leans this novel toward the young adult market is the lively treatment of this very weighty subject and the fact that the hero succeeds.—Kristianne Huntsberger