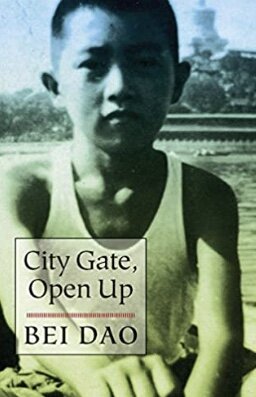

City Gate, Open Up by Bei Dao, translated by Jeffrey Yang (New Directions Books)

Few books have surprised me as much as Bei Dao’s memoir of growing up in Beijing in the 1950’ s and 60’s. I picked it up certain that I was going to be faced with another “misery memoir,” tales of cruelty and deprivation during China’s Great Step Forward and Cultural Revolution. Instead this book recreates Beijing as it once was, an account steeped in the world of the senses and told through the point of a view of a child.

When he returns after a thirteen-year absence in 2001, as his plane prepares to land in the city that had been his home, he’s dazzled by the light that sprawls below him, “like a huge, glittering soccer stadium.” In the houses of his childhood, there was no lighting stronger than 14 watts and some bicyclists when traveling at night lit their way by carrying paper lanterns. The darkness was a time for playing hide-and-seek, telling stories, acknowledging the presence of ghosts. The new glare of fluorescent light immediately makes him “a foreigner in my own hometown.”

His hometown from the past is rebuilt with the precision and beauty of a poet, which is what Zhao Zhenkai has become famous for, writing volumes of poetry under the pen name Bei Dao. History is a dim background to the sense memories that Zhao uses to reconstruct his neighborhood in Beijing, a place filled with the smell of coal smoke and dust. The seasons are marked by other odors: winter is characterized by the smell of white cabbage, which every family buys in amounts of almost four hundred pounds, peeled, sun-dried, and stacked as a bulwark against months of cold and hunger. Spring is announced by the blossoms of apricot, pear, and peach trees, their fragrance “so intense it made people dizzy, lulling them to sleep.” Summer has the faint perfume of the yellow flowers of pagoda trees followed by autumn’s smell of chalk dust and fallen leaves with their “bitter aroma of strong tea.”

His neighborhood rings with village noises: the crowing of a neighbor’s rooster, the cries of street vendors, the sounds of wagon wheels and horses’ hooves on the pavement, the “ruckus” of cicadas, those “pure noisemakers.” One night another boy takes Zhao to a a dark street where he hears the “disordered cilp-clop” of a herd of donkeys that will soon be food for the carnivores in the zoo.

Food is a recurring theme that takes on greater strength with each chapter. Childhood treats of frozen icepops and White Rabbit candy with its edible rice-paper wrappers, along with the horror of cod liver oil that’s doled out every morning, give way to a savage hunger. Discarded vegetable trimmings that Zhou gathers to feed his pet rabbits are confiscated by his mother and turned into the family’s supper. Later, before the rabbits die of starvation, his father kills them to provide a feast that Zhao and his siblings tearfully refuse to eat. Boys dive for freshwater clams in a city lake to augment the cabbage and yam diet that has made the neighborhood swell with dropsy.

Childhood games of shooting marbles, rolling hoops, and spinning tops become subsumed in the excitement of lighting firecrackers that turn into battles with gangs of boys besieging each other, “as if we were preparing for a war.” “The day the Great Cultural Revolution Broke out, I remembered the pungent smell of my first firecracker.”

And when life changes forever on June 1, 1966, “countless boys and girls served as the source of that energy.” At first the Cultural Revolution feels like a game that frees students from facing examinations. “All classes were dismissed, the term over; I cheered with relief, flitting about like a joyful sparrow,” Even when he and his family take his parents’ cache of banned books from the attic and burn what Zhao had regarded as his treasure, he feels “a stealthy thread of delight.”

“I became king of the children,” and Zhao leads his neighborhood gang to the home of a man rumored to have once fought with the Kuomintang. Gleefully they shave his head and imprison him in a basement for days. “After that, bumping into him on the street was like meeting a ghost.”

What had been a childhood that echoed Dylan Thomas’s memories of Christmas in Wales is warped into Golding’s Lord of the Flies. “His bold vision,” Zhao says, had been a ruthless reality for us.” “The stench of blood spread across Beijing” and violence shattered the city that had been a childhood idyll.

But in 2010, I experienced three seasons in the same area that Zhao grew up in. In the evening, little stone houses on narrow streets gleamed with dim squares of light, trees furled in emerald canopies along the lake where he used to play, old men in an outdoor market sold bamboo cages that held crickets, on weekends women held bouquets of balloons for sale. And everywhere there was food in glorious abundance: piles of fresh pineapple, stalls where women made pancakes to order, bakeries filled with cakes and cookies, and the omnipresent smell of grilled lamb skewers. Everywhere I went I saw children, eating.

What was lost? What’s been gained? Who can measure this? But thanks to Bei Dao/Zhao Zhenkai, we can remember a world we’ll never know..~Janet Brown