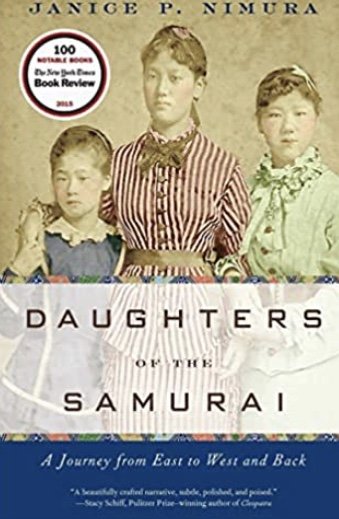

Daughters of the Samurai: A Journey from East to West and Back by Janice P. Nimura (W.W. Norton and Company)

The wife of the Meiji Emperor Mutsuhito, Empress Hiroko, was by all accounts a child prodigy. When she was three she could read, she wrote poetry by the time she was five and was a student of calligraphy at seven. Now at 22 in 1871, she is “a modern consort” who joins her husband in welcoming the opening of Japan to Western industry and education. Under her patronage, five Japanese girls are chosen to live in the U.S for ten years, all expenses paid by Japan, with the goal of receiving Western educations and returning to teach women in their country.

Of the five, only one has any familiarity with English; six-year-old Ume is able to say “Yes. No. Thank you.” None of them are able to communicate with the American woman chosen as their chaperone during the voyage nor with the stewardess who was meant to bring them food and clean their cabin. Until one of the Japanese diplomats finally comes to check on them, the girls live on the boxes of desserts that were given to them as gifts when they boarded the ship.

In America the girls qre treated as exotic curiosities in San Francisco and on the train journey that takes them to Washington DC. On the train, they are so entranced by the vast outstretches of snow that the oldest becomes snowblind, damaging her eyesight so badly that she’s sent back to Japan along with the girl closest to her in age. Now the remaining three are headed by eleven-year-old Sutematsu, followed by Shige who’s just ten and Ume who had turned seven soon after arriving in the states. The 24-year-old diplomat who had traveled and lived abroad for years and was described as “a Westerner born of Japan” is horrified when the girls are presented to him, especially taken aback by Ume. “They have sent me a baby,” he says with an undiplomatic display of horror.

It becomes obvious that the girls need to be placed in separate homes if they are ever to learn English and become acculturated to Western ways. Ume remains in Washington with a childless couple who immediately welcome her as their daughter. Sutematsu is placed with the family of a Yale professor and Shige in the home of one of the professor’s friends. All three quickly adapt to the freedom and comfort of Western clothing and and the unaccustomed softness of pillows that aren’t made of wood. Although their hosts receive money for their upkeep, the arrangements made for each girl are “more familial than financial” and within a year of their arrival in America, they have become part of their American families.

They flourish, becoming adept at croquet, chess, and lawn tennis. Ume, alone without Japanese friends, begins to forget her language. Sutematsu has a brother attending Yale who’s adamant that she remain Japanese, keeping her “moral code,” which he ensures by giving his sister lessons in Japanese culture, history, and language. Shige’s family welcome a young Japanese student into their household who is smart, handsome and four years older than Shige. He provides an incentive for her to practice her native language as well as giving her a reason to look forward to returning home.

After several years at Vassar, she is the first one to go back to Japan at the end of her ten year commitment, engaged to the handsome student. Not as driven as the other two girls, Shige happily becomes a piano teacher in Tokyo.

Sutematsu however is an academic star. Both she and Ume apply for an additional year in the U.S. in order for them to graduate, Ume from high school and Sutematsu with a bachelor’s degree from Vassar. On the voyage home, they’re both apprehensive. Ume, high-spirited and indulged, finds herself wishing that the missionary passengers aboard ship were “not quite so quiet or good.” Sutematsu, when considering her imminent homecoming, says, “I cannot tell you how I feel but I should like to give one good scream.”

Japanese public opinion has changed in the decade the girls had spent in America. Western ideas and education are viewed by many as a threat and the idea of educating Japanese daughters is being challenged. Shige, happily married and with limited ambition, repatriates with little difficulty. Sutematsu quickly discovers that marriage is the way to repay her debt to her family and her government. When a highly placed nobleman proposes, she puts aside her idea of having her American sister join her in Tokyo, with the two of them forming an independent household and launching a Western school together, and marries a man much older than she. “What must be done is a change in the existing state of society, and this can only be accomplished by married women,” she writes to her “sister” in America.

Ume has become thoroughly American and she refuses to give that up. Her value, as she perceives it, is in her mastery of the English language--no matter that she’s without any real fluency in Japanese. Her ambition is to be a spinster, independent with a teaching career, but she soon discovers that in Japan there is no word for spinster and old maids are pitied and disdained. Her stubborn willfulness pays off however. While Sutematsu’s brilliance is turned to the service of enhancing her husband’s career and Shige becomes blissfully domestic, it’s Ume who uses her charm and her determination to become an educator whose name is still known in Japan, with her family name emblazoned on Tsuda College for women and her accomplishments taught in elementary school social studies classes.

Janice Nimura has constructed a framework for the lives of these girls, delving deep into the tradition and history of the samurai class from which they came. Sutematsu was the one most steeped in this background of rigid discipline, having lived through the war between royalist progressives and feudalist warlords when she was old enough to help her family make the bullets that may have wounded her future husband. It was her iron-bound training that made her diverge from the career she trained for into the life of nobility, where her influence extended to establishing charity bazaars and hospital volunteers among the aristocracy. Ume, who had little discipline imposed upon her before her American life, was the one to break through traditional barriers, the ones that Shige welcomed. The stories of three displaced girls and how they prevailed and succeeded is one that deserves greater attention than it’s been given, and through Nimura’s skill and scholarship, this has finally taken place~Janet Brown