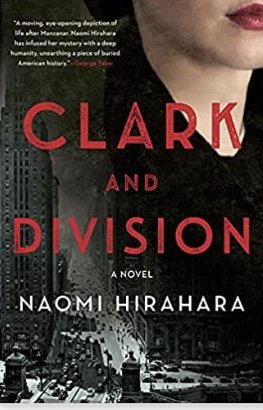

Clark and Division by Naomi Hirahara (Soho Press)

When Aki and her parents get off the train in Chicago, a city they’ve never seen before, they’re greeted with the news that Rose, the family’s oldest daughter, won’t be there to meet them. On the day before, Rose died. It’s suicide, the police tell them. She leaped into the path of an approaching subway train.

Newly released from the California internment camp of Manzanar, the Ito family is overwhelmed with culture shock as well as grief. Rose had been the family leader, beautiful, smart, and confident. She was the one who became active in the JACL, the Japanese American Citizens League, after the Itos had been sent to Manzanar and she was one of the first to be released from internment. She had found a job in Chicago and a place for her family to live as soon as they were allowed to follow her. Now she’s dead, leaving her younger sister to take her place.

Aki refuses to believe that Rose killed herself. As soon as her family settles into their new apartment, she begins to track down the people who had known her sister, the ones who might help to explain the circumstances around her death. In her search, she discovers dark depths to the recently established Japanese population and urban corruption that appears to be untouchable.

Clark and Division is a gripping mystery, a rite of passage story, and a journey into past history that’s illuminating and shocking. Naomi Hirahara is a journalist as well as an Edgar Award-winning novelist and the research she’s done for her latest book is deep and revealing, disclosing facts that have been ignored.

Even before the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor sent Japanese Americans to internment camps, the discrimination against them was crippling. Those who had been born in Japan, the Issei, were unable to buy or lease land in Los Angeles. White women, as well as American-born Nisei women, who married Issei men were stripped of their U.S. citizenship. After war had been declared on Japan, Executive Order 9066 in 1942 demanded the removal of all Japanese residents, “alien and non-alien,” from California, Washington, Oregon, and parts of Arizona, where the city of Phoenix was split in half to facilitate the emptying of Japanese neighborhoods. Japanese, Issei or Nisei, who had been educated in Japan were sent to Department of Justice detention centers. All others went to one of the ten internment camps where blocks of barracks held families, with separate Children’s Villages constructed for orphans.

As the need for cheap labor became acute, by 1943 “loyal” Japanese were released to take jobs vacated by the men who had gone off to war. Even then they weren’t allowed to return home. They were banned from the Western Military Zone and were sent to midwestern and eastern cities that needed laborers and had a scant Japanese population. This resettlement was overseen by the War Relocation Authority which aided the new arrivals with housing, employment, and education, while demanding that the Japanese congregate in public only in groups of no more than three. In private, they were crammed into subdivided rooms in apartments and small studios, with often as many as six people in a single room.

Although World War Two ended in September, 1945, the last internment camp wasn’t closed until seven months later. The scars left behind by the internment are widely overlooked and the facts about the enforced creation of Japanese communities in cities like Chicago have been buried for the past eighty years. At the same time that Naomi Hirahara has Aki uncover the truth behind her sister’s death, she skillfully reveals hidden corners of American history, with a back-of-the-book list of resources for readers to use in their own research. Let’s hope for Aki’s appearance in books yet to come that will disclose buried history while unfolding more of her own compelling story.~Janet Brown