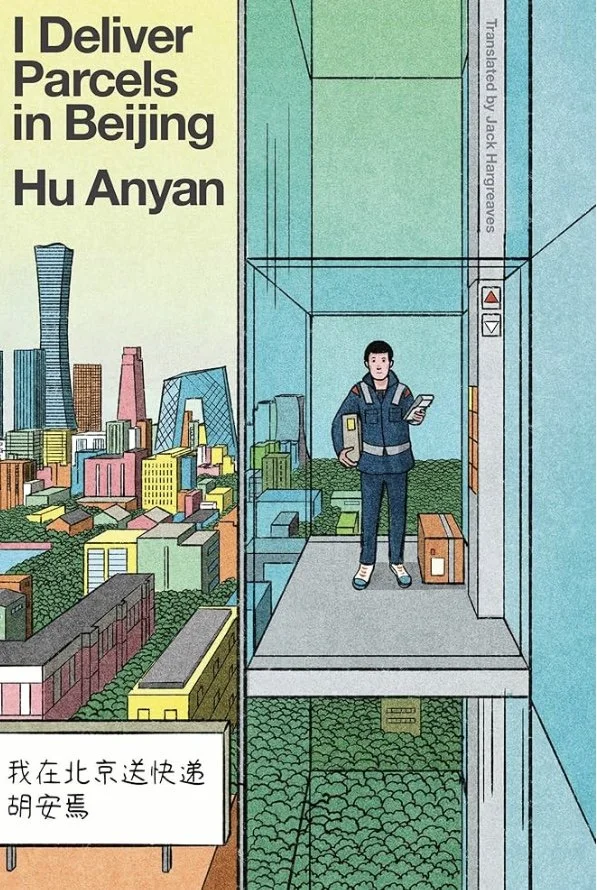

I Deliver Parcels in Beijing by Hu Anyan (Astra House) ~Janet Brown

In China, Double Eleven and Double Twelve are two of the main commercial festivals. Double Eleven is a celebration for those who are single, giving themselves gifts and taking themselves out for dinner and a movie. Double Twelve is ostensibly a counterpart for couples, while actually it's the brainchild of online megasellers, Taobao and TMall, a way to stimulate e-commerce at the end of the year. This is when delivery couriers "start earning real money," as Hu Anyan is told when he tenders his resignation shortly before the onslaught of gift-giving begins.

Hu doesn't care. In his three months of working as a courier for one of Beijing's largest parcel delivery services, "the Haidilao of couriers," he has submitted to an unpaid three-day trial period, received a position as a contract worker with no benefits or insurance, and worked for weeks without a delivery trike, making his rounds on foot. A case of pneumonia has cost him a large amount of his monthly paycheck and his workday is brutally long. Taking a job at a smaller delivery service with shorter workdays and full insurance coverage is an easy decision. After all, he reasons, "What more do the poor really have to lose?"

Hu begins to examine the value of his work. All tasks not directly related to delivery are his fixed costs that make him no money. In order to reach his "desired wage," he has to complete a delivery every four minutes. Using a restroom costs him one yuan, so he cuts back on drinking water. A lunch break of twenty minutes costs him ten yuan, with the additional price of the food making this too expensive, so he forgoes lunch most of the time. "I became suddenly, painfully aware that time is money, " and he begins to "take time for myself." After work, he reads.

His choice of literature comes as a surprise. This man whose job essentially turns him into a human robot doesn't read comic books or martial arts thrillers. When he picks up a book at night, it's James Joyce's impenetrable classic Ulysses and The Man without Qualities by Robert Musil. Later in his narrative, when he tells about jobs he's had in the past before delivering packages, he reveals surprises. He's worked at a firm that produces 3D architectural drawings, learning Photoshop and AutoCAD. He's been an anime artist and a graphic designer for a comic book publisher. He's had his own business. He spent time in Beijing as an artist, living a bohemian lifestyle. He's a published writer and a voracious reader of "American realism," devouring books by J.D. Salinger and Raymond Carver. He becomes a follower of Hemingway's "iceberg theory" that advocates leaving eighty percent of a story hidden, discovered only by careful readers. When covid arrives with its enforced isolation, Yu begins to write online and his work attracts magazine editors.

It's only in his final pages that this man reveals part of the iceberg, showing his intellectual side, his thoughts on freedom, and his commitment to his work as a writer. "Freedom," he decides, "is largely a matter of consciousness, and not of what you possess."

The surprise that comes from reading his book is how much more freedom a Chinese worker has than an American laborer. Wages are low but jobs are so plentiful that Hu leaves one place of employment for another easily, without worry. Rent is cheap enough that he always has a place to sleep; homelessness isn't part of his narrative. He's able to afford food and medical care when he needs it and when he decides to move to another city, he does that without apprehension. When his work is contrasted against accounts written by American workers for e-commerce giants, Hu's life is the one to envy.