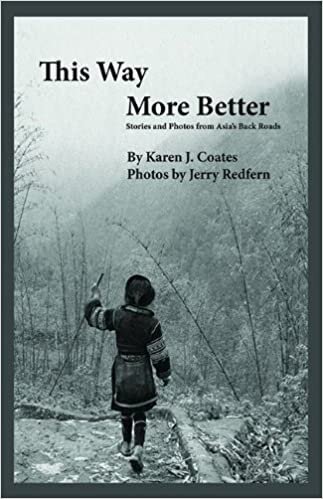

This Way More Better : Stories and Photos from Asia's Back Roads by Karen J. Coates (ThingsAsian Press)

Karen J. Coates loves traveling. You may find this hard to believe but she’s been traveling since she was seven! It’s true. Coates tells us in her own words, “The journey began on the family room floor of a middle-class Midwestern home.” She continues, “There I sat on the green shag carpeting with the pages of National Geographic spread before me.” She tells herself, “I want to go there and there and there. I want to write that and that and that.”

That is exactly what she does. First, she studies as a grad student in Hanoi, After graduating, she takes a job writing for a newspaper in Phnom Penh, Cambodia and she has been traveling ever since. You can read her writing in the pages of National Geographic, Travel + Leisure Southeast Asia, the Wall Street Journal Asia and Fodor’s Travel Guide.

This Way More Better is a collection of her essays covering about a dozen years from 1998 to 2010. Coates and her photojournalist husband, Jerry Redfern, travel extensively throughout Southeast Asia. Their travels take them through Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia and the newly independent nation of East Timor. She meets the people and shares their stories, their dreams, their desires, and their way of life. Accompanying many of the essays are black and white and color photos taken by Redfern.

In 1999, in the Vietnamese border town of Sapa near China, Coates meets Shu, a ten-year-old Hmong girl who is also an innovative entrepreneur. She befriends Coates and her husband and becomes their guide. Conversations are made in broken English and by using gestures. Coates learns that Shu takes tourists on walks and sells the handmade crafts made by her parents. The American duo also make a trip into the forest to see firsthand the effects of the illegal logging industry which supports the villages and families of the Hmong people and other hilltribes.

In Laos, they visit the famous Plain of Jars, a unique archeological site where over three-thousand jars or stone vessels were discovered. Some of the jars are very large, measuring over nine feet in height and weighing in the tons. They are also informed that the Plain of Jars is considered one of the most dangerous archaeological sites not because of the jars themselves but because of the massive amounts of unexploded ordnance, UXOs that are leftover from the Vietnam War.

One of the most fascinating stories Coates writes about is Aunty Glen, an Australian woman, friends says runs a homestay in the jungle. The place is located in a small town called Pilok, Thailand, only a few short kilometers away from Myanmar. Coates has never met Aunty Glen but she is told, “She has an oven.” “She bakes cakes.” “They’re the best in Thailand.”. What better excuse does she need to make a visit

You will enjoy this small collection of stories about the people Coates and her husband meet and the places they visit. They meet Dr. Dan, a man who runs a clinic in Dili in East Timor. They are invited to the coronation of Cambodia’s newest king. They sip tea in northern Thailand.

In 2009, Coates receives an unexpected email The sender is none other than Shu, the ten year old Hmong girl, introduced in the first essay of the book. The story of their reunion is a highlight that will stick with you long after you’ve set the book down.

Each story in this book is unique. Although the essays are not written chronologically, they do have a certain order that is unique to Coates. She sums it up best in her introduction when she says, “Books often offer a vacation from life. I hope, instead, this book takes you traveling.” Bon Voyage! ~Ernie Hoyt

Available from ThingsAsian Books